Cultural Production in Larissa Sansour’s Sci-Fi Trilogy

Nation Estate is a 2013 Palestinian sci-fi short film directed by Larissa Sansour. It screened at the London Palestine Film Festival and was reviewed for PCF.

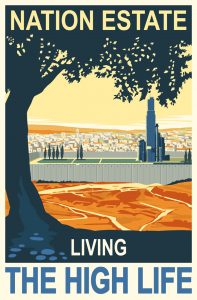

Larissa Sansour’s Nation Estate might just as easily be an e-State. In the film, the state of Palestine has been displaced and located within a single high rise building; the skyscraper is organised by touch-screens and facial recognition systems, swift and seamless elevator shafts, keycards and marble floors. A place where the only voices are tannoyed and the governing is algorithmic. Where interaction is cold, clean and faceless, and citizens stare straight ahead in atomised proximity.

Each Palestinian region is contained and segmented onto a different floor, connected only by elevator shaft. It’s a place where the appurtenances of the nation state are equally broken off, packaged and made to stand still — what happens to immaterial notions of identity, tradition, community when they are trapped and on display like subjects in a police line-up? The answer seems to be simple. Nothing.

Frantz Fanon notes the tendency of culture, in the context of oppression, to fall into representationalism. Cultural products can often become ‘the inert already forsaken result of frequent, and not always very coherent, adaptations of a much more fundamental substance which is itself continually being renewed…mummified fragments which because they are static are in fact symbols of negation and outworn contrivances’.

Nation Estate is saturated with mummified fragments, and it’s not surprising that the clinical, modernist efficiency of the high rise immediately draws comparisons with another locus of mummification—the museum. Nowhere else but for the museum do we see medieval architecture sequestered within cold marble. The protagonist, played by Sansour, exits the elevator shaft onto her floor—Jerusalem—which sits against a brutal white backdrop, as if it were a permanent museum exhibit. All that’s missing is a short descriptive paragraph pinned below the Dome of the Rock. In the following scene we see, in her apartment, a cupboard full of homogenous, tinned food, ready-made falafels and tabbouleh, literally preserved, destined to remain in a time-warp, forever the same everywhere but for in the collective imagination of the Estate’s residents. What is ready-made is unchangeable. Like the high-rise, the food is unable to grow but for ‘upwards’. It can only ever expand via a kind of constant self-replication, ever-more mythic and ever-harder to see from the ground.

The genre Sansour chooses to work in is always generous. Science fiction frees the artist from their contemporary restrictions by challenging them to invent new realities. Of course, new realities confront old ones, which lays bare the notion that the contemporary is always an ongoing process of invention, made up of a patchwork of political and economic narratives. It marks an engagement with what’s known as de-fetishisation; the process of making reality seem contingent and thus changeable provided you have the right tools.

In another film, A Space Exodus, we see a new kind of political narrative in play. A reworking of The Moon Landing—one of the most symbolically charged ‘events’ pertaining to the mastery of capitalism—becomes ‘one small step for a Palestinian, one huge leap for mankind.’ Sansour riffs off Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: Space Odyssey but with arabesque musical influences—a film which is not so much trying to construct new symbolism as it is about that process of symbol-making. Which is always a process, and is always associated with power. The film is playful and there’s a pleasure in being given the opportunity to think about this kind of reality. As in In The Future They Ate From The Finest Porcelain, where characters bury porcelain is deep into the ground to imply a different kind of past to future archaeologists, Sansour commits to the notion that narrative construction is itself a type of struggle.

During a Q&A at the London Palestine Film Festival, Sansour, in response to a question about the role of the Palestinian artist, is quick to disavow her films from politics—or from pre-existing political narratives—because, she says, those have all been expressed already. The purpose of science fiction is to seek out the unsaid, the new and the strange. The result is that we might remember that everything was at some point new, and everything continues to be strange.

Al John is a postgraduate student living in London. He has written for OpenDemocracy, 3:AM Magazine, Adbusters and elsewhere.

The London Palestine Film Festival runs 16-28 November 2018

palestinefilm.org.uk