Palestinians re-enact prison trauma in film Ghost Hunting

After a two year break, the London Palestine Film Festival has returned, with a packed ten day programme across the city.

The festival opened on Friday 16 November at The Barbican with a screening of Ghost Hunting followed by a Q&A with the film’s critically acclaimed director Raed Andoni. The film picked up the main documentary prize at The Berlin International Film Festival and was Palestine’s entry for Best Foreign Language Oscar at the 2018 Academy Awards.

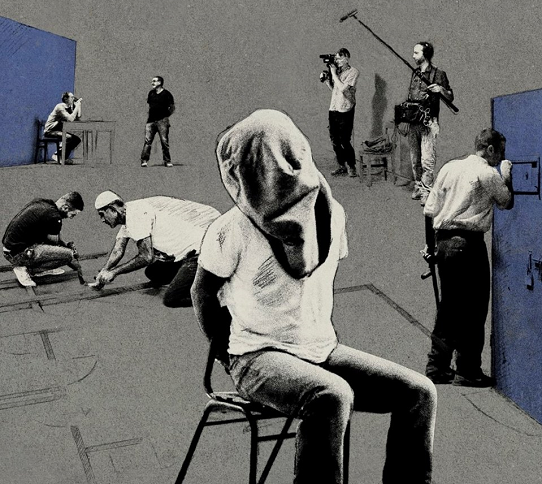

Ghost Hunting may well raise a few eyebrows for its ethically ambiguous premise. A group of former Palestinian prisoners reconstruct an Israeli interrogation and detention centre in a warehouse in Ramallah, primarily based upon Jerusalem’s notorious al-Moskobiya.

The participants, who all willingly volunteered for the process, play out their experiences from prison, in turn playing interrogator and prisoner during scenes depicting verbal, physical and sexual abuse, all based on their actual experiences from time in Israeli jails.

In fact, having originally scripted the film, Andoni scrapped this on the first day of filming, realising the real life stories carried more weight and emotion than fiction ever could.

Andoni explained how during filming he would outline a scenario and then ask for volunteers to play it. When stepping into the role of interrogator, the men unleashed the pain and trauma that had once been inflicted on them back onto the prisoners, often using verbatim lines they recalled being said to them. The result is incredibly raw and powerful, with the men at once both captor and captive.

Two psychologists were employed as part of the crew to ensure no further harm was caused to participants’ mental health and the men knew they could leave the process at any time. But even within the realms of this relatively safe and controlled environment, this is a highly disturbing and unsettling watch.

As director, Andoni was as much a part of this process as the others, having too shared the experience of incarceration as a teenager. With one in four Palestinians having passed through Israeli detention centres, Andoni remarked how this is simply part of the collective Palestinian experience. He recalled sitting in the cell and weeping uncontrollably when making this film. He believes it is because he shares in this collective experience that the film works as well as it does and the men were able to reach the depths of emotion they do. The men trusted him, he said, and even allowed him to be violent with them.

Andoni is not suggesting that in re-enacting their trauma, the former prisoners will somehow exorcise and be freed from their demons. “The only solution to trauma is to accept that your ghosts will follow you and become part of your life,” he said, sardonically referring to his own sat beside him on the stage.

But the film suggests some catharsis is achieved by at least acknowledging the demons are there. It suggests some strength may be drawn in collectively expressing the things they have been through. Andoni shared how after the film’s screening in Ramallah, a large audience made up mostly of former prisoners stayed behind for over two hours sharing their prison stories with one another.

There is often a glorification of prisoners in Palestine and Andoni spoke of clichéd language we have become used to using around the subject. One audience member expressed hope the film would serve as a springboard for talking about Palestinian prisoners’ mental health, and the mental health of Palestinians in general.

Despite the fact that an estimated 10,000 Palestinian women have been arrested and/or detained over the last 50 years (Addameer), Ghost Hunting deals almost exclusively with the experience of the Palestinian male prisoner. Though the film fell short of much acknowledgement of the female prisoner’s experience, it was not a total erasure as towards the end a young woman visited the set and shared with the attentively listening group her own recollections from six months in an Israeli detention centre, in a cell she described as even smaller than any in this recreation.

Ghost Hunting does not serve as an informative documentary about Palestinian prisoners. It is a raw experiment: confrontational, upsetting and at times tittering on the edge of acceptability.

The group went through different motions during the experiment, which Andoni described as revealing layers. By the end, they were sat together joyfully talking about their loved ones. “All the love came in the end. It became beautiful. I didn’t want the film to finish. I would have loved to stay another two months because it became an amazing place where we were sharing stories about fiancées, wives, their love stories, their kids,” described Andoni.

Azza el-Hassan, who chaired the conversation, expressed perfectly, “You get the feeling that they’re damaged characters, but they’re not broken.”

The London Palestine Film Festival runs 16-28 November 2018

palestinefilm.org.uk

No Comments